To gain the knowledge of the Runes and its deep meaning, no price was too high for the Allfather.

Odin’s self-imposed ordeal began as he hung himself from a branch of Yggdrasil, pierced by his own hand with his trusty spear, Gungnir. For nine days and nights He hung between life and death, peering down to the Well of Urd – the source of fate. From the depths of the well the Allfather saw the drawings made by the Norns, the damsels of fate, until he finally understood them and thus gained the knowledge of the Runes and of Fate itself.

The tale of Odin’s sacrifice is first told in the Old Norse poem Hávamál, “The Sayings of the High One”:

I know that I hung

On the wind-blasted tree

All of nights nine,

Pierced by my spear

And given to Odin,

Myself sacrificed to myself

On that pole

Of which none know

Where its roots run.

No aid I received,

Not even a sip from the horn.

Peering down,

I took up the runes –

Screaming I grasped them –

Then I fell back from there.

The tree from which Odin hangs himself is Yggdrasil, the world-tree at the center of the Germanic cosmos, whose branches and roots hold the Nine Worlds. Directly below the world-tree is the Well of Urd, a source of incredible wisdom. The runes themselves seem to have their native dwelling-place in its waters. This is also suggested by another Old Norse poem, the Völuspá, “Insight of the Seeress”:

There stands an ash called Yggdrasil,

A mighty tree showered in white hail.

From there come the dews that fall in the valleys.

It stands evergreen above Urd’s Well.

From there come maidens, very wise,

Three from the lake that stands beneath the pole.

One is called Urd, another Verdandi,

Skuld the third; they carve into the tree

The lives and fates of children.

Large wooden statues of the Norns at a museum in Ribe, Denmark

Runes were never considered to be merely as letters for the Vikings, but as having potent virtues within themselves of a metaphysical or even magical nature.

The Norse and other Germanic peoples used the runic alphabet since the first century, but they did not use this writing the way we do now, or even the way Mediterranean and other neighboring cultures did then. Instead, runes were for inscriptions of great importance.

Rather than being penned on vellum or parchment, runes were usually carved on wood, bone, or stone, hence their angular appearance. Carved on sticks or other objects, they could be cast and deciphered to discern the present or predict the future. They could be carved into runestones to commemorate ancestors and mark the graves of heroes. Because they had inherent meaning, they could be used as a means of communication between the natural and supernatural, and could thus be used as spells for protection or success.

While evidence suggests that most Vikings could read the runes on at least a basic level, for them the true study and understanding of these symbols was a pursuit fit for the Gods.

Runic Futharks

Our word alphabet comes from the Greek letters alpha and beta. Similarly, modern experts have termed runic alphabets futharks (or futhorks), based on the first six letters of Elder Futhark which roughly correspond to our F, U, Th, A, R, and K. Elder Futhark earns its designation because it is the oldest-discovered complete runic system, appearing in order on the Kylver Stone from Gotland, Sweden, dated from the dawn of the Migration Era (around the year 400).

Kylver Stone from Gotland

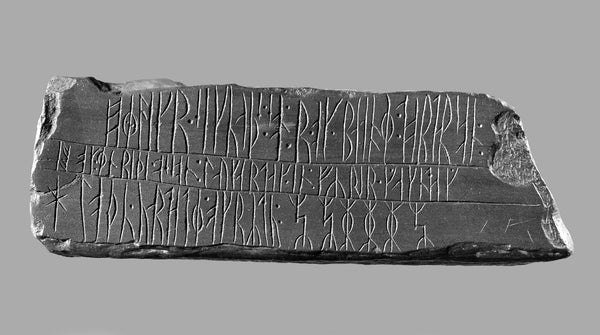

Runestones were often raised next to grave sites within the Viking era of 950-1100AD and roughly 50 of them have been found so far. Some of the raised runestones first appear in the fourth and fifth century in Norway and Sweden with most of them found in Sweden. In Denmark they were found as early as the eighth and ninth century, with more than a few Runestones found in Greenland, such as the Kingittorsuaq Runestone.

Kingittorsuaq Runestone

Elder Futhark has 24 runes, and over the next few centuries became widely used amongst the many Germanic tribes that vied for survival throughout Europe. By the Viking Age (roughly, 793-1066) the Elder Futhark gradually gave way to the Younger Futhark. The Younger Futhark has only 16 runes, not because the language was becoming simpler but because it was becoming more complicated. Phonetically, the runes of the Younger Futhark were working double-duty to cover the changes that were differentiating the Norse tongues from that of other Germanic peoples.

Younger Futhark can be further divided into styles, including the 'long branch' (Danish) and the 'short twig' (Swedish and Norwegian) runes:

The explosion of trade and interaction brought about by the Viking Age created an increased need for writing and literacy, thus archaeologists have cataloged thousands of inscriptions in Younger Futhark while we only have hundreds in Elder Futhark. While seers and völva priestesses still used the runes to perceive the paths of the cosmos, we have found many runic inscriptions that were related to law or trade, or simply a man or woman carving their name on a personal item. Of course, the Vikings also left runic graffiti from Orkney to Constantinople and beyond as they pushed the boundaries of their world ever-further.

Reading and Writing Runes

The following tables offer a quick and basic introduction to the runes used by the Vikings and their ancestors. These charts should serve for those looking to transliterate their names or other epitaphs or to find known associations with particular meanings. Many books and other resources are available for deeper inquiry, but there is much about runes that is not known.

The similarities between many of the original Elder runes and today's English letters is undeniable. Much more than a writing system, the runes exerted a great influence in the Norse daily life, as sacred to Odin as his ravens Hugin and Munin, thought and memory.

Try writing your name in runes in the comments below!

Sources:

Flowers, Stephen E. 1986. Runes and Magic: Magical Formulaic Elements in the Older Runic Tradition. ISBN-13: 978-0820403335

Crawford, Jackson. 2019. The Wanderer's Havamal, ISBN-13: 978-1624668357