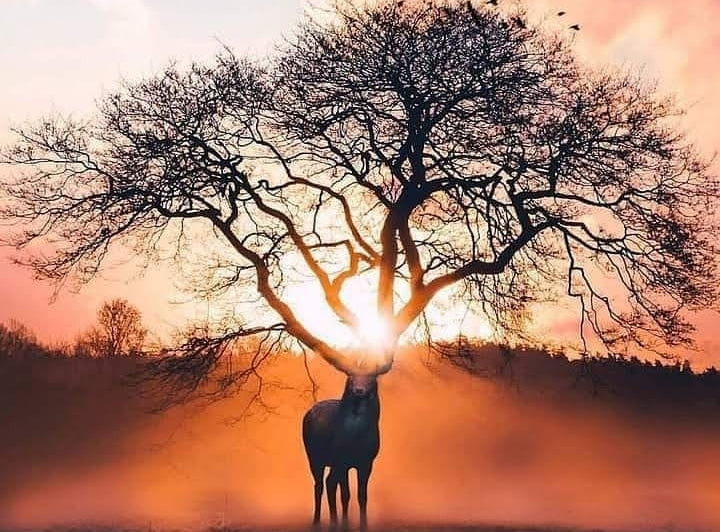

The mighty tree Yggdrasil is the center of the Norse cosmos, supporting all of the nine realms in place. Yggdrasil is also the home of several fantastic beasts, linked forever with the fate of the great tree.

Numerous animals are said to live among Yggdrasil’s stout branches and roots. Around its base lurk the dragon Nidhogg and several snakes, who gnaw at its roots. An unnamed eagle perches in its upper branches, with a hawk named Veðrfölnir on its brow, and a squirrel, Ratatoskr (“Drill-Tooth”), scurries up and down the trunk conveying the dragon’s insults to the eagle and vice versa. Meanwhile, four stags – Dainn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr, and Durathror – graze on the tree’s leaves.

Amusing though some of these animals and their activities may be, they hold a deeper significance: the image of the tree being nibbled away little by little by several beasts expresses its mortality, and along with it, the mortality of the cosmos that depends on it.

Most of the information regarding Yggdrasil and its inhabitants come from the Poetic Edda, compiled by Snorri Sturluson. According to the Edda, the first root of Yggdrasil is located in Helheim, deep below the thick ice of Niflheim.

Near this root there is a well, called Hvergelmir (Old Norse “bubbling boiling spring”). Both the Prose Edda and the poem Grímnismál explain that the dragon Níðhöggr (Meaning: Hateful Striker) alongside countless snakes live in this well and in this root.

Níðhöggr is constantly chewing on Yggdrasil's root, in an attempt to topple the mighty tree. He only stops when he hears the Hell hound Garmr howling in the distance, which announces the arrival of new dead souls in Helheim. Upon hearing the wolf's howls, the dragon briefly stops chewing and flies down to the entrance of Helheim, where he lands next to the newly arrived souls, and sucks the blood out of all the corpses until they turn completely pale. Please bear in mind that this part was written in the 13 century, under heavy Christian influence.

Níðhöggr is not alone at the root, with many snakes to keep him company. From the Lay of Grimnir (Grímnismál):

More snakes

lie under the ash Yggdrasil

than any old fool imagines.

Going and Moin,

they are Grafvitnir’s sons,

Grabak and Grafvollud, and Ofnir and Svafnir

will always, I believe

eat away the tree’s shoots.

– Grímnismál 34

At the top of Yggdrasil lives a giant eagle. Not much is known about the eagle, but it has been described in the Prose Edda to possess knowledge of many things. The eagle must be a lot bigger than a normal eagle because between its eyes sits a hawk named Vedrfolnir (Old Norse: Veðrfölnir).

Between the eagle at the top and the dragon at the root, lives a squirrel, named Ratatoskr (Meaning: Drill Tooth). When Níðhöggr is chewing on Yggdrasil’s root he is often interrupted by Ratatoskr who fills his ears with insults. Ratatoskr is an annoying squirrel who has nothing better to do than to run up and down the tree between the dragon and the eagle on the top.

Every time the eagle makes an insult about Níðhöggr, the squirrel will run down the tree and tell the dragon what has been said about him. Níðhöggr is just as rude in his own comments about the eagle and, upon hearing the new insults, he replies back at the squirrel with his own insults about the eagle. Ratatoskr’s involvement as a carrier of these messages keeps the hatred between Níðhöggr and the eagle alive, and he is the sole reason why they remain constant foes.

The hawk Vedrfolnir siting between the eyes of the great eagle is possibly associated with the knowledge of the eagle. He may, just like Odin’s two ravens Huginn and Muninn, fly out to gather knowledge. Although, it is only according to Snorri Sturluson that there are both a hawk and an eagle at the top of the world tree, so this part is uncertain.

Among the green branches of the mighty tree live four stags, their names are Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Duraþrór, who spend their days busily devouring the leaves from the tree.

Four harts also

the highest shoots

ay gnaw from beneath:

Dáin and Dvalin,

Duneyr and Dýrathrór.

– Grímnismál 33

The names of the stags mean Dáinn, “The Dead One”; Dvalinn “The Unconscious One”; Duneyrr “Thundering in the Ear” and Duraþrór “Thriving Slumber”. Early suggestions for interpretations of the stags included connecting them with the four elements, the four seasons, or the phases of the moon, and even the winds.

Over the roof of Valhalla (Old Norse: Valhöll) dwell two more creatures: the goat Heidrun (Old Norse: Heiðrún) and the stag Eikthyrnir (Old Norse: Eikþyrnir). The stag spends its day eating the new cuttings from the tree, while the goat eats the leaves.

From the udders of the goat flows endless streams of mead into a big tub in Valhalla. Every evening, after the warriors in Valhalla finish their training and practice battle for Ragnarök, they will sit down in this hall to relax, eating the meat from the giant pig called Sæhrímnir and drink the mead from the goat.

Sæhrímnir is a mighty boar, killed and eaten every night by the Æsir and the Einherjar (literally “army of one”, “those who fight alone”, warriors slain in battle and chosen to dwell in Valhalla). The cook of the Gods, Andhrímnir, is responsible for the slaughter of Sæhrímnir and its preparation in the cauldron named Eldhrímnir. After Sæhrímnir is eaten, the beast is brought back to life again to provide sustenance for the following day.

Sources:

Jesse Byock (2005) Snorri Sturluson, The Prose Edda. 1st. edition. London, England: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN-13 978-0-140-44755-2

Anthony Faulkes (1995) Snorri Sturluson, Edda. 3rd. edition. London, England: Everyman J. M. Dent. ISBN-13 978-0-4608-7616-2

Lee M. Hollander (1962) The Poetic Edda. 15th. edition. Texas, USA: University Research Institute of the University of Texas. ISBN 978-0-292-76499-6

Magnusson, Finnur, Den Ældre Edda: En samling af de nordiske folks ældste sagn og sange (1821–23), Paperback – November 26, 2011 ed. ISBN-13: 978-1272170158